Turks in Saudi Arabia

الأتراك في السعودية Suudi Arabistan Türkleri | |

|---|---|

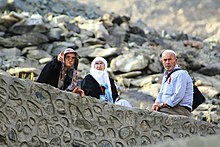

A group of Turkish pilgrims at Jabal Thawr to perform umrah | |

| Total population | |

Total: 270,000-350,000 Turkish minority (Ottoman descendants only): 150,000[1] Additional modern Turkish immigrants: 120,000-200,000[2][3][4] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Riyadh, Jeddah, Mecca | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Turks in the Arab world, Syrians in Saudi Arabia |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Turkish people |

|---|

|

Turks in Saudi Arabia also referred to as Turkish Arabians, Turkish Saudi Arabians, Saudi Arabian Turks, Arabian Turks or Saudi Turks (Turkish: Suudi Arabistan Türkleri, Arabic: الأتراك في السعودية) refers to ethnic Turkish people living in Saudi Arabia. The majority of Arabian Turks descend from Ottoman settlers who arrived in the region during the Ottoman rule of Arabia. Most Ottoman Turkish descendants in Saudi Arabia trace their roots to Anatolia; however, some ethnic Turks also came from the Balkans, Cyprus, the Levant, North Africa and other regions which had significant Turkish communities. In addition to Ottoman settlement policies, Turkish pilgrims to Mecca and Medina often settled down in the area permanently.

There has also been modern migration to Saudi Arabia from the Republic of Turkey as well as other modern nation-states which were once part of the Ottoman Empire.

History

[edit]Ottoman migration to Arabia

[edit]The Turkish presence in Saudi Arabia can be traced historically from the bastions of the Arabian Peninsula painted of Ottoman dominion in past centuries. The Ottoman Empire, which arose in the 13th century starting in the Middle East and Europe, expanded in the 16th century to cover almost the entire Arabian Peninsula, including the two holy cities of Mecca and Medina. Turkish domination of today’s Saudi Arabia began at this period and continuing on towards Ottoman rule. The Ottoman leadership of the area was mainly accomplished by appointing local influentials; however, the empire also deployed a network of Turkish soldiers, administrators and academics to garrison these territories and secure the pilgrim routes.

During this period, many Turks emigrated to Hijaz, especially to the cities of Mecca, Medina, and Jeddah; some their descendants are still living there. The Ottomans brought along with them architectural styles, culinary traditions, and systems of education into this land and mixed them with the local Arab culture. This period of Ottoman rule lasted until the early 20th century despite intermittent local rebellions and tensions. The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire following World War I brought a redrawing of the Middle Eastern borders, and in the 1920s, Abdulaziz Al Saud founded the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Thus, after huge Ottoman influence in the region, yet the many-centuries-long Ottoman presence had left its mark, and Turkish cultural traits could be found in the architecture, the cuisine, and some of the local customs of Saudi Arabia. In recent years, with the strengthening of the diplomatic and economic relations between modern Turkey and Saudi Arabia, a new wave of Turkish nationals to Saudi Arabia has emerged, mainly for work in the construction, education, and health sectors, further enriching the historical Turkish presence. Today, though not overwhelmingly numerous, Turkish people and culture are still woven into the fabric that is responsible for the diversity and shared history of Saudi Arabia on the Arabian Peninsula.

Politics

[edit]During the 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum, more than 8,000 Turkish expats from Saudi Arabia cast votes whether Turkey should abolish its parliamentary system and become a presidential republic.[5] 58.34% of the Turkish expatriates in Saudi Arabia opted for "No", while 41.66% voted for "Yes". The yes vote was concentrated in Jeddah and the Western Region, while in Riyadh no was the dominant choice. The no vote wassignificantly higher compared to votes of several European Turkish expat communities.[6]

Religion

[edit]Turkish people living in Saudi Arabia are Sunni Muslims. Turkish laborers returning from Riyadh seem to be less likely to espouse Shariah (Islamic law) than those living in European countries.[7]

Notable people

[edit]- Kamal Adham, businessman (Turkish mother)

- Iffat Al-Thunayan, princess and the most prominent wife of King Faisal

- Princess Sara, activist for women and children welfare

- Prince Mohammed, businessman

- Princess Latifa

- Prince Saud, served as Saudi Arabia's foreign minister from 1975 to 2015

- Prince Abdul Rahman, military officer and businessman

- Prince Bandar, military officer

- Prince Turki, chairman of King Faisal Foundation's Center for Research and Islamic Studies

- Princess Lolowah, prominent activist for women's education

- Princess Haifa

- Mohammed bin Faisal Al Saud, businessman

- Reem Al Faisal, photographer

- Faisal bin Turki Al Faisal Al Saud

- Abdulaziz bin Turki Al Faisal, racing driver and businessman

- Reema bint Bandar Al Saud, Saudi Arabian ambassador to the United States

- Khalid bin Bandar bin Sultan Al Saud, Saudi Arabian Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- Faisal bin Bandar bin Sultan Al Saud, president of the Saudi Arabian Federation for Electronic and Intellectual Sports (SAFEIS) and the Arab eSports Federation

- Omar Basaad, music producer

- Muhammad Khashoggi, medical doctor

- Adnan Khashoggi, businessman

- Samira Khashoggi, author and the owner and editor-in chief of Alsharkiah magazine

- Soheir Khashoggi, novelist

- Dodi Fayed, film producer

- Emad Khashoggi, businessman and the head of COGEMAD

- Jamal Khashoggi, general manager and editor-in-chief of Al-Arab News Channel

- Nabila Khashoggi, businesswoman, actress, and philanthropist

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Akar, Metin (1993), "Fas Arapçasında Osmanlı Türkçesinden Alınmış Kelimeler", Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi, 7: 94–95

- ^ Harzig, Juteau & Schmitt 2006, 67

- ^ Koslowski 2004, 41

- ^ Karpat 2004, 12

- ^ "More than 1 million Turkish expats vote in charter referendum - Turkey News". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ "Referendum divides Turkish expats". Saudigazette. 2017-04-18. Retrieved 2021-03-01.

- ^ Gerald Robbins. Fostering an Islamic Reformation. American Outlook, Spring 2002 issue.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ergener, Reşit (2002), About Turkey: Geography, Economy, Politics, Religion, and Culture, Pilgrims Process, ISBN 0-9710609-6-7.

- Fuller, Graham E. (2008), The new Turkish republic: Turkey as a pivotal state in the Muslim world, US Institute of Peace Press, ISBN 1-60127-019-4.

- Hale, William M. (1981), The Political and Economic Development of modern Turkey, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7099-0014-7.

- Harzig, Christiane; Juteau, Danielle; Schmitt, Irina (2006), The Social Construction of Diversity: Recasting the Master Narrative of Industrial Nations, Berghahn Books, ISBN 1-57181-376-4.

- Jung, Dietrich; Piccoli, Wolfango (2001), Turkey at the Crossroads: Ottoman Legacies and a Greater Middle East, Zed Books, ISBN 1-85649-867-0.

- Karpat, Kemal H. (2004), Studies on Turkish Politics and Society: Selected Articles and Essays:Volume 94 of Social, economic, and political studies of the Middle East, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-13322-4.

- Koslowski, Rey (2004), Intnl Migration and Globalization Domestic Politics, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-203-48837-7.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (1997), Trends in International Migration: Continuous Reporting System on Migration: Annual Report 1996, OECD Publishing, ISBN 92-64-15508-2.

- Papademetriou, Demetrios G.; Martin, Philip L. (1991), The Unsettled Relationship: Labor Migration and Economic Development, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-25463-X.

- Sirageldin, Ismail Abdel-Hamid (2003), Human Capital: Population Economics in the Middle East, American University in Cairo Press, ISBN 977-424-711-6.

- Unan, Elif (2009), MICROECONOMIC DETERMINANTS OF TURKISH WORKERS REMITTANCES: SURVEY RESULTS FOR FRANCE-TURKEY (PDF), Galatasaray University